Prehistoric dental treatments were extremely rare, with a few documented cases from the Neolithic era. Early farming as well as an increase in carbohydrate-rich diets are said to be the cause of an increase in carious lesions, the researchers noted (Scientific Reports, July 16, 2015).

Egyptian texts confirm Ancient Greeks and Romans had removed caries by drilling and cleaning the infected cavity, at least in the fifth century B.C.

At the time, toothpicks likely made of bone or wood were used to remove food particles between teeth. These new findings may demonstrate how early humans adopted the ‘toothpicking’ technique. Other early forms of dentistry included scratching caries using microlithic points, which are small stone tools usually made of flint or chert, typically about a centimeter long and half a centimeter wide.

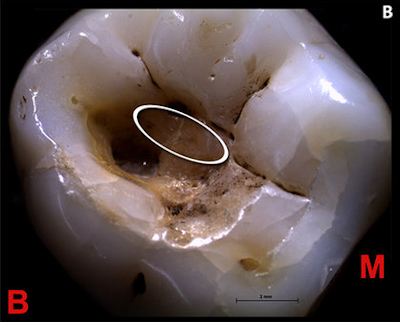

In 1988, an international team of researchers found a well-preserved 25-year-old male skeleton in a burial site in Villabruna, Italy. On this specimen, they analyzed a lower right third molar and discovered a tooth that retains a large occlusal cavity with four carious lesions.

“Various scientific analyses confirm that the vast carious lesion found on the chewing surfaces of the lower right third molar was intentionally treated, probably to clean out the infected tissue, through the use of a stone tip that left deep streaks on tooth enamel around and inside the cavity,” stated Jacopo Moggi-Cecchi, an associate professor from the department of biology at the University of Florence.

“The earliest dental caries manipulation entails an adaptation of the toothpicking technique from simple rubbing actions between interproximal teeth using probes made on bone/wood, to scratching/levering activities within the carious lesion using microlithic points,” the authors said.

There were traces of residue in the cavity, suggesting that it may have been filled with a natural wax, possibly beeswax, which could have been found in the area nearby, according to the study.

Chewing likely caused the tooth enamel to become partially rounded and polished, indicating the treatment was performed long before the young man passed.

“This study suggests that primitive forms of carious treatment in human evolution entail an adaptation of the well-known toothpicking for levering and scratching rather than drilling practices,” the authors wrote.

“The Villabruna specimen represents, therefore, the oldest archaeological evidence of operative manual intervention on a pathological condition (caries), as indicated by the striations on the bottom of the carious pit, potentially to remove the caries and/or to reestablish antagonistic tooth function by removing food particles entrapped within the cavity,” the study authors concluded.

Sources: Dr.Bicuspid.com, Scientific Reports